Robert Wiene | 77 mins | Blu-ray | 1.33:1 | Germany / silent (German) | U

The poster child for German Expressionist cinema, as well as featuring “cinema’s first true mad doctor” and “cinema’s first unreliable narrator” (at least according to David Cairns on the Masters of Cinema Blu-ray — I haven’t verified those statements for myself), The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari certainly has a lot to unpack for a film that’s barely an hour-and-a-quarter long. Or does it? Because one has to wonder if there’s an element of style over substance here.

“A mystery story told in the Poe manner,” according to the original Variety review, the titular Dr Caligari (Werner Krauss) is the host of a fairground attraction, and his eponymous cabinet contains Cesare (Conrad Veidt), a somnambulist who Caligari controls — at the fair, to answer questions from the audience; and at night, to do his evil bidding, including murder. Caligari’s activities come to the attention of young Franzis (Friedrich Feher), who attempts to uncover the truth about the doctor and expose him.

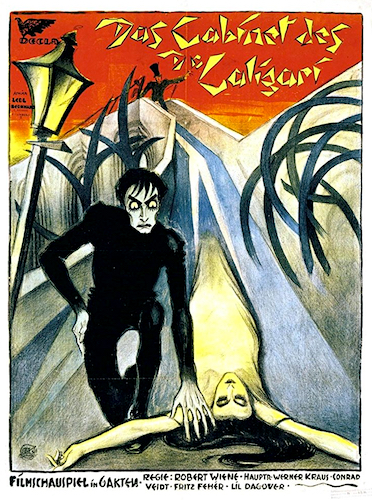

But the most famous thing about Caligari by far is not the storyline or the characters, but the visual style. Painted backdrops evoke a landscape straight out of a nightmare: jagged lines and stark monochromatic shapes (this isn’t just a film that happens to be filmed without colour, it feels black and white), they give the impression of the winding streets of a town and its locales without actually being one. The implied structures tower over the characters, leaning in above, creating an oppressive and unnerving atmosphere, while their total lack of reality evoke theatre more than the literalism we’re now used to from film. The make-up and performances are the same: heightened; dreamlike — or nightmarish.

Which may be entirely appropriate given the film’s framing narrative, which (spoilers!) introduce an ending that’s a little bit “and it was all a dream”. Or was it? Well, that depends how you interpret what happens. The bookends were apparently added to help sell the film to the public, framing its fantastical narrative in something more grounded. The screenwriters weren’t happy — as Lotte H. Eisner writes (in the MoC booklet), “the result of these modifications was to falsify the action and ultimately to reduce it to the ravings of a madman. The film’s [screenwriters], Carl Mayer and Hans Janowitz, had had the very different intention of unmasking the absurdity of asocial authority, represented by Dr. Caligari.” Well, the tacked-on ending doesn’t necessarily negate such an interpretation, you just need to fill in the blanks to get there yourself.

For example, there’s what Cairns calls his “Mulholland Drive theory”: that what we witness is all true, until the point that Franzis sees the asylum director is Caligari; from there until the reveal that Franzis is an asylum patient is a fantasy. Evidence in favour of this: everything goes implausibly swimmingly for our hero in that section, from easily recruiting the asylum staff to finding (as Cairns puts it) “Caligari’s second cabinet, in which he keeps his entire backstory.” It’s a fun reading, even though it’s clearly a case of projecting an interpretation onto the film that wasn’t intended by the makers.

One that fits better, perhaps, is that Franzis’ flashbacks aren’t merely “the ravings of a madman”, but he’s telling the truth, and that somehow between the end of his flashbacks (which see Caligari locked up in his own asylum) and where we join the framing narrative (with Franzis locked in the asylum and Caligari in charge), the evil doctor has reasserted his authority and captured his accuser. Of course, that requires a leap — how does Caligari regain control? Why don’t we see it happen? Well, we don’t see it happen because that wasn’t what the makers intended.

And so we come back to “it was all a dream”. Maybe that’s the best explanation — the writers may’ve hated it, but in some respects it saves them from themselves: Cairns’ visual essay highlights a bunch of plot holes, inconsistencies, and confusions, not to mention issues of character motivations and actions (“in a way it makes no sense to speak of character motivation in a mad man’s fantasy”), all of which you can hand-wave away if “it was all a dream”. This is why I wondered if it was style over substance. The sets, the make-up, the performances — all fantastically atmospheric. The story, the characters, their actions — not such great shakes.

But maybe that’s okay. After all, why not? Director Robert Wiene and his crew did a fantastic job of bringing a surreal nightmare to life, and nightmares seldom feature plausible storylines.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari was viewed as part of my Blindspot 2017 project, which you can read more about here.