To promote his new movie, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, writer-director Quentin Tarantino has curated a selection of movies from the Columbia vault (because Columbia is owned by Sony, and Sony are releasing OUaTiH) that are in various ways connected to said new movie. Some are influences on its style; some are the kinds of movies that the film’s characters would’ve appeared in; some speak to the societal concerns of the era. Along with film writer Kim Morgan, QT has hosted a “movie marathon” of his ten picks on TV, broadcast in the run-up to OUaTiH’s release in various territories (it’s on Sony-owned channels in 60 countries, and has been sold to other broadcasters in 20 more — “check local listings for details” and all that).

It’s been on this past week in the UK, airing nightly at 11:30pm on Sony Movie Channel, finishing with a double-bill tonight. If you’ve missed it, Movies4Men are repeating the lot next week from 6:30pm. I’m away from home this weekend so will have to catch some of those repeats, but I did watch the films on earlier in the week, and here are some thoughts on the first two…

(If you watched this series elsewhere and are thinking “but those weren’t the first two films,” you’re right: for no apparent reason they’ve juggled the order in the UK.)

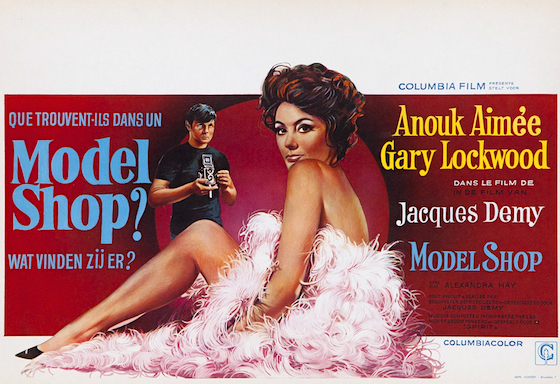

(1969)

Jacques Demy | 97 mins | TV | 16:9 | USA & France / English

The English-language debut of French writer-director Jacques Demy, Model Shop shows us a day in the life of George (2001’s Gary Lockwood), a 26-year-old whose disillusionment is ruining his life. He’s quit his job at an architect’s because it was too low-level — he wants to design the big stuff, but isn’t interested in putting in the work to get to that tier. Consequently his girlfriend is getting fed up with him, he’s in debt, and his beloved car is about to be repossessed. George manages to talk the repo man into giving him until the end of the day to find the $100 he owes, and so he sets off on a drive around L.A. to find a friend to borrow it from. That’s when he spots a mysterious glamorous woman (Anouk Aimée) and begins to follow her.

That perhaps makes the film sound more focused than it seems in viewing. There’s a definite European sensibility in play here — a laid-back, wandering feel, as George drifts around L.A. in his car, meeting up with different friends in different situations. The possibility of the draft hangs over their heads, informing their actions. As Morgan and Tarantino discuss in their introduction, some people might view the conversations and speeches in the film as being unnecessarily ‘heavy’, but it’s more than mere existentialism when there’s a genuine life-or-death experience just an unwanted call-up away.

The atmosphere all that creates can make the film feel aimless, but, as Tarantino puts it, “the more you talk about Model Shop, the more you realise there is more to talk about.” Even while it feels like nothing is happening, stuff is happening. It’s the kind of film where we’re accumulating knowledge about the character and his world, and sometimes it’s only with hindsight we realise its signficance. At first it may not even seem like there’s much of a story — what could pass for the inciting incident (needing to acquire $100) is actually solved relatively quickly — but there is definitely a story, even if it’s a relatively small, somewhat undramatic one. This combination is I think why Tarantino describes the film as “deceptively simple and deceptively complicated.” I suppose it depends how much you want to see; how much you want to engage.

Personally, I found George to be an immensely, almost painfully relatable character. The way he doesn’t quite know what he wants to do, just what he doesn’t; the way he doesn’t want to put in the long slog, just jump to the more interesting stuff at the end; the way he drifts and kills time rather than doing anything useful; and his big speech after he’s made to consider his own death “for the first time in [his] life”: he’s not a coward, but he doesn’t want to lose his life, because what’s better than life? Only, perhaps, art that reflects it. I’m not saying I am George, exactly, but boy, there were reflections.

I was less engaged by Anouk Aimée’s character, Lola, who, once she’s properly introduced, takes over somewhat. Turns out she’s a character from Demy’s debut feature, Lola, making this a sort of sequel — only “sort of” because, while Model Shop does continue her story, she’s not at all the focus. Apparently a lot of Demy’s films feature crossover characters and connections in this way, which I guess was also an inspiration to Tarantino.

I’d not heard of Model Shop before it cropped up in Tarantino’s selection, and it’s not been classified by the BBFC since its original release, so I presume it’s never had a video / DVD / etc release in the UK. While I would hardly say it’s some kind of ‘lost’ masterpiece, it does evoke a place and a time and the kind of lives that may’ve lived there — which is precisely why QT showed it to his Once Upon a Time crew, for the way it depicted L.A. in 1969 (he reckons it’s possibly the best movie ever for showing Los Angeles). Some of it is interesting, but at other times it retains that sense of aimlessness. It’s far from meritless, but I can also see why it’s the kind of film that’s been half forgotten.

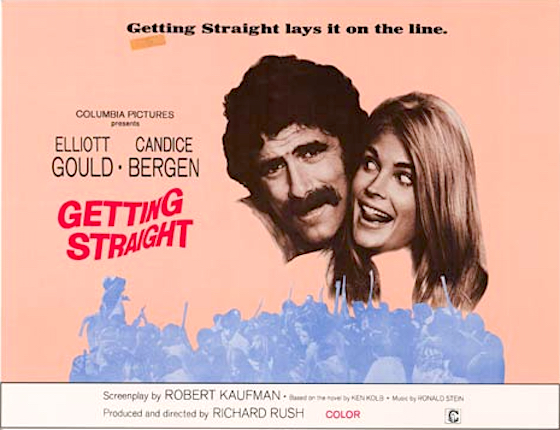

(1970)

Richard Rush | 120 mins | TV | 16:9 | USA / English | 15 / R

According to Quentin Tarantino (I suppose I could try to independently verify this, but I haven’t), Getting Straight is one of four “campus radical” movies that were all released in 1970 (the other three are Zabriskie Point, R.P.M., and The Strawberry Statement). It stars Elliot Gould as Harry Bailey, a post-grad student at an unnamed Californian university, where he intends to qualify as a teacher, but where he’s also revered by the other students for his history of activism — even as he’s basically trying to join the establishment, they’re trying to lure him back to his old radical ways, beliefs he hasn’t left behind but doesn’t seem to wholly stand by anymore… or does he?

So Harry is, on the surface, a potentially interesting main character: someone caught between the revolutionary youth and the establishment; who tells the youth why they’re dreaming and deluded, and tells the old men why they need to listen and buck up their ideas; but who is, therefore, conflicted about his own place in it all. But while putting someone in the middle might seem like a fair why to argue for both sides, it’s a bit obvious; allowing the film to have its cake and eat it, to an extent. And while it might seem objectively true that Harry is conflicted, evidenced by his flip-flopping from side to side, he seems pretty sure of himself for most of the film. There’s little done to explore his fence-sitting; to question his status as someone who proclaims to believe certain things yet seems to still find himself sat in the middle. Is he a hypocrite? If he is, I’m not sure the film bothers to interrogate that. So, if he isn’t, is that just because the film doesn’t want to show him as one? Perhaps we’re meant to buy that he’s the only sane person in a mad world, which seems a bit of a cliché.

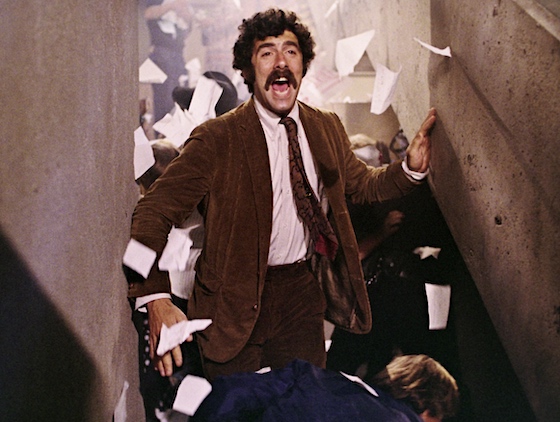

At the end Harry does ultimately pick one side, dramatically rejecting the establishment to go join rioting students. Why? He’s goaded into snapping by a professor’s smug, self-satisfied interpretation of The Great Gatsby, but if we’re meant to know why this bugs him so then I missed it. Does he reject the reading? Is it the tone of it, which is like being lectured down to? Maybe it’s just the straw that broke the camel’s back, but I didn’t really follow that as an arc. Earlier in the film Harry talks about finding a student riot sexy, a turn on, and then the movie ends with him and his girlfriend stripping off to shag literally in the middle of a riot, which does make you wonder if he was just thinking with his dick. I mean, he was for half of the rest of the film.

With its focus on Harry, Getting Straight is something of a character study, and if this is anyone’s film it’s Gould’s. At times he gets a chance to expose different sides of this divided person, but he also certainly does a lot of shouting, lecturing, and ranting in the role. So maybe instead it’s about the times, with Harry basically a cipher to explore pertinent issues and different sides. It’s based on a 1967 novel, so was a relatively prompt adaptation, though to remain timely it would’ve had to be. Then again, Leonard Maltin’s movie guide apparently describes it as a “period piece”, and there’s a point there: the film is so much about that specific point in time that it couldn’t be set anytime else. Along with the slightly detached view of its main character, it doesn’t seem to be in or of the moment, like you might expect from a countercultural film made during the actual counterculture. It’s reflecting on it, like a period movie.

Getting Straight is “one of [Quentin Tarantino’s] favourite movies ever,” or so he says, which unfortunately is a sentiment I can’t get on board with. I’m not even sure I can stretch to giving it a passing grade, because it was a bit too freewheeling and, by the end, in spite of the climactic ranting and rioting, kinda boring.

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is in UK cinemas from Wednesday, 14th August.